More than one in five students in U.S. public schools have some kind of learning disability. But if you ask teachers, parents, or even school psychologists which one shows up the most, the answer is almost always the same: dyslexia.

Dyslexia Is the Most Common Learning Disability

Dyslexia isn’t about seeing letters backward. That’s a myth. It’s a neurological difference that makes it hard for the brain to connect spoken sounds with written letters. Kids with dyslexia struggle to sound out words, recognize familiar ones quickly, and spell accurately-even when they’re smart, curious, and work hard.

According to the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, dyslexia affects about 15-20% of the population. That means in a typical classroom of 30 students, 4 to 6 kids are likely dealing with it. It’s the most common reason kids get referred for special education services in reading.

What makes dyslexia stand out is how early it shows up. By second grade, kids with dyslexia often lag behind in reading fluency. They might read slowly, guess words based on shape, or avoid reading out loud. But they usually understand stories just fine when someone reads to them. That mismatch-strong thinking skills but weak reading skills-is a classic sign.

Why Dyslexia Gets Missed

Many kids with dyslexia fly under the radar because they’re quiet, polite, and try too hard. Teachers might think they’re just “not trying” or “not gifted in reading.” Parents might assume their child will grow out of it. But dyslexia doesn’t go away on its own. Without the right support, kids fall further behind each year.

Another reason it’s missed? It doesn’t always come with obvious signs like behavior problems. Kids with ADHD might fidget or zone out. Kids with dyslexia often sit quietly, staring at a page, silently struggling. They’re not lazy-they’re exhausted.

Some schools wait until third or fourth grade to test for reading issues. That’s too late. Research shows that early intervention-before age seven-is the most effective. The brain is more flexible then. With the right teaching method, most kids with dyslexia can learn to read at grade level.

How Dyslexia Shows Up in School

Dyslexia doesn’t just show up in reading. It shows up everywhere language is involved:

- Struggling to remember the order of days of the week or months

- Confusing similar-looking letters like b/d or p/q

- Slow, choppy reading-even after years of practice

- Spelling the same word five different ways on one page

- Difficulty following multi-step directions

- Avoiding reading assignments or pretending to forget books

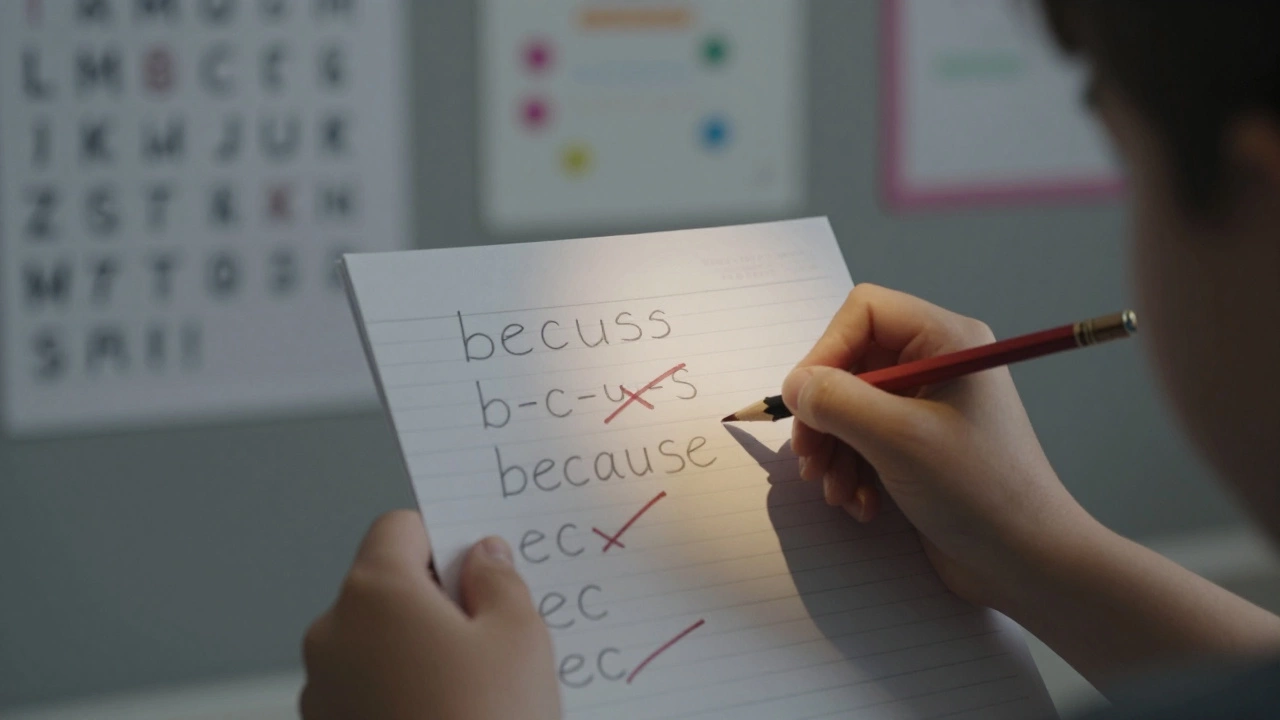

These aren’t choices. They’re symptoms. A child who spells “because” as “because,” “becuz,” and “b-c-u-s” isn’t being careless. Their brain is processing language differently.

What Works: Evidence-Based Teaching

Not all reading programs help kids with dyslexia. Phonics? Yes. Whole language? Not enough. The most effective approach is structured literacy-explicit, systematic, and cumulative teaching of phonemes, decoding, spelling, and vocabulary.

Orton-Gillingham, Wilson Reading System, and Lindamood-Bell are three well-researched methods. They break language into tiny pieces and teach them step by step. Kids don’t just memorize-they learn how words are built. They learn why “cat” sounds like /k/-/a/-/t/ and why “thought” doesn’t sound like “t-h-o-u-g-h-t.”

These methods aren’t magic. They take time. But studies from the National Reading Panel and the International Dyslexia Association show that with consistent, daily instruction, 70-80% of kids with dyslexia can reach average reading levels by fifth grade.

It’s Not Just About Reading

Dyslexia doesn’t stop at reading. Many kids with dyslexia also struggle with writing. They know what they want to say, but putting it on paper feels impossible. Handwriting is messy. Spelling gets in the way. They might avoid writing assignments altogether.

That’s why accommodations matter. Text-to-speech software. Extended time on tests. Speech-to-text tools. Allowing oral responses instead of written ones. These aren’t “cheats.” They’re equalizers. They let the child show what they know without being punished for how they process language.

One high school teacher in Ohio told me about a student who wrote brilliant essays aloud but couldn’t type them. Once he was allowed to record his answers, his grades jumped from Ds to As. He wasn’t lazy-he was blocked by a system that didn’t adapt to his brain.

Myths That Hurt

There are so many myths about dyslexia:

- “It means you’re not smart.” → False. Many people with dyslexia have above-average IQs.

- “It’s just a phase.” → False. It’s lifelong, but manageable.

- “Only boys have it.” → False. Girls are underdiagnosed because they’re quieter.

- “It’s caused by too much screen time.” → False. It’s genetic and neurological.

These myths delay help. They make kids feel broken. They make parents feel guilty. They make teachers feel helpless.

The truth? Dyslexia isn’t a defect. It’s a difference. Many people with dyslexia think in pictures, see patterns others miss, and solve problems in creative ways. Richard Branson, Steve Jobs, and Agatha Christie all had dyslexia. They didn’t overcome it-they learned to work with it.

What Parents and Teachers Can Do

If you suspect a child has dyslexia, don’t wait. Start by:

- Observing patterns: Does the child avoid reading? Mix up sounds? Spell inconsistently?

- Talking to the school: Ask about screening tools like the DIBELS or the CTOPP.

- Requesting an evaluation: Under federal law (IDEA), schools must evaluate if there’s reason to suspect a disability.

- Looking for a certified specialist: Not all tutors are trained in structured literacy. Ask if they’re certified by the International Dyslexia Association.

- Using assistive tech: Apps like NaturalReader, Grammarly, or Microsoft Immersive Reader can make a huge difference.

And most importantly-don’t stop believing in them. Kids with dyslexia need to know they’re not behind. They’re just on a different path.

Other Learning Disabilities-Just to Be Clear

Dyslexia is the most common, but it’s not the only one. Other learning disabilities include:

- Dyscalculia: Trouble with numbers and math concepts. Affects about 5-7% of students.

- Dysgraphia: Difficulty with writing. Often overlaps with dyslexia.

- ADHD: Not a learning disability, but often co-occurs. Affects focus, organization, and impulse control.

- Language Processing Disorder: Trouble understanding spoken language, even with normal hearing.

These are all different. They need different supports. But dyslexia is the one you’re most likely to see.

What Happens After School?

Dyslexia doesn’t disappear after graduation. But with the right tools, people with dyslexia thrive in college, careers, and life. Many become entrepreneurs, artists, engineers, and doctors.

Colleges now offer accommodations automatically if students provide documentation. Employers are required by law to make reasonable adjustments. The key is knowing your rights and speaking up.

One former student told me: “I didn’t know I had dyslexia until I was 22. By then, I’d failed three college classes. But once I got text-to-speech and extra time, I graduated with honors. I didn’t change. The system finally caught up.”

Is dyslexia the same as a reading delay?

No. A reading delay means a child is behind but catching up with normal instruction. Dyslexia is a neurological difference that doesn’t improve without targeted, structured teaching. Kids with dyslexia often stay behind unless they get specialized help.

Can a child outgrow dyslexia?

No. Dyslexia is lifelong. But with the right instruction, kids can learn strategies to read, write, and spell effectively. They don’t outgrow it-they learn to work around it.

Do all kids with dyslexia struggle with spelling?

Almost all do. Spelling requires remembering letter-sound patterns, which is hard for brains wired for dyslexia. Even adults with dyslexia often spell words incorrectly, but they can use tools like spell-checkers and speech-to-text to manage it.

Can a child with dyslexia be good at math?

Yes. Many kids with dyslexia excel in math, especially if it’s taught visually or conceptually. Dyslexia affects language processing, not logic or reasoning. Some become strong problem-solvers because they think in patterns and images.

What’s the best age to test for dyslexia?

By the end of first grade, if a child isn’t recognizing letter sounds or blending simple words like “cat” or “dog,” it’s time to look closer. Early screening tools can spot risk as early as preschool. Waiting until third grade means missing the best window for intervention.